Balzac and the Protocols: A Stylometric Analysis

By Lawrence Erickson

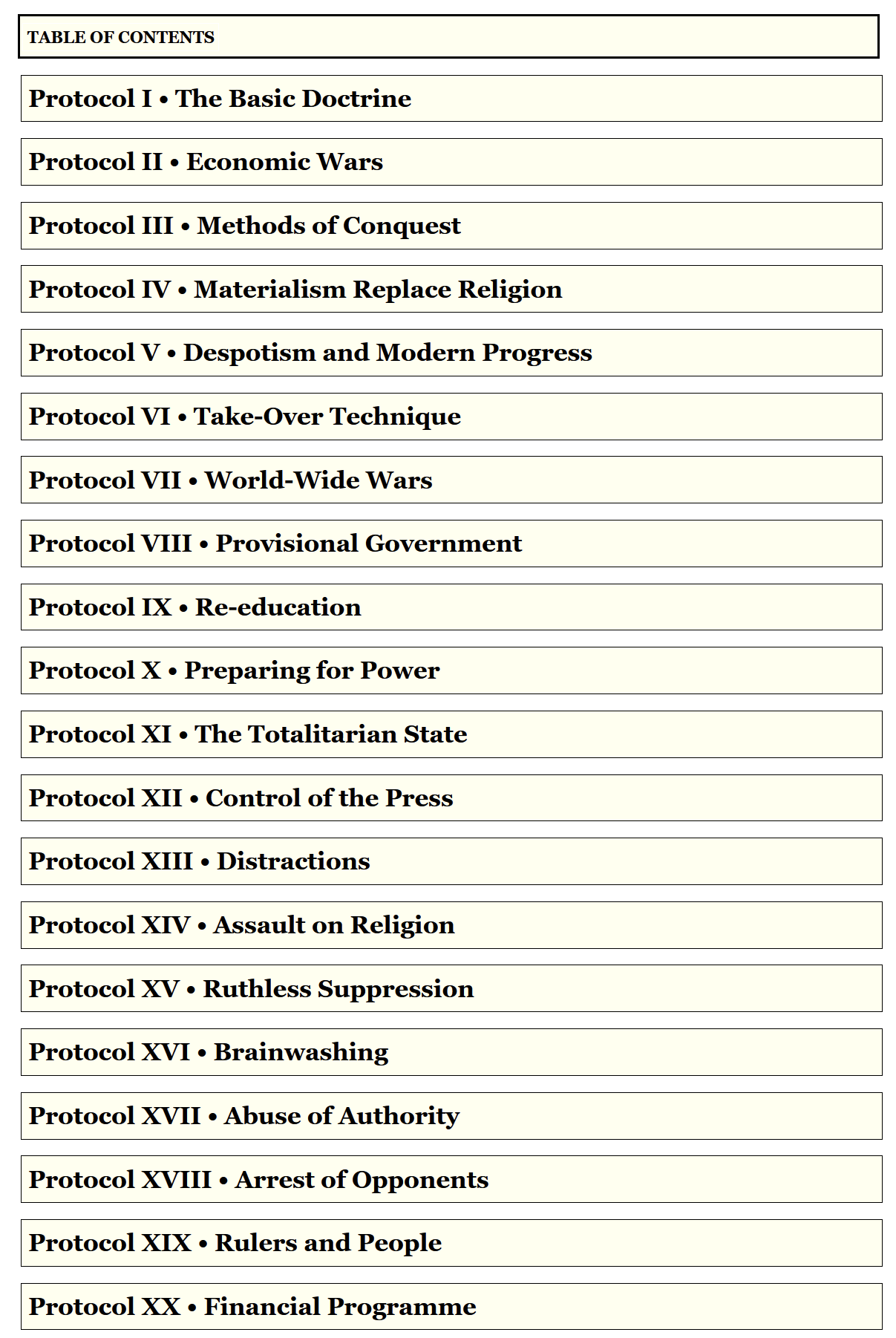

The mysterious document entitled The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion captivated millions at the beginning of the 20th century, and a fierce debate broke out over whether the document was an actual recording of a speech given by a Jewish conspirator or simply a concocted piece of propaganda.

The latter side seemed to score a decisive victory when it was shown that the Protocols overlapped significantly with an obscure 1864 French work by Maurice Joly, surely proving that Tsarist operatives had ripped from this work for the sake of advancing their political objectives.

However, what was rarely considered was the possibility that the plagiarism was reversed, and that it was Joly who stole from an older and unpublished version of the Protocols. In my first article on this topic, I made the case that Honoré de Balzac wrote the Protocols during the tumult of the 1848 revolution in France. My analysis though was based entirely on Balzac’s Human Comedy, and so I thought it may be lucrative to do more research into some of Balzac’s more obscure works.

Shortly after starting, I discovered a couple of them that were assembled into a book together. The first was called Modern Government, published in 1833, and the second was an unpublished work called Essay on Power, and the introduction writer believes it was written around 1841. Modern Government didn’t provide too much of interest, but I did notice a couple additional parallels. In the first, the same analogy of the nation as a horse and the ruler as the rider is used:

Just imagine the ineptitude of the masses and yet continue to give them influence in the government! France once shook off her cavalier, or collapsed beneath him from exhaustion, refusing him to take a final step under her spur. With the Emperor dead, all his ideas are understood.

The Protocols:

It is precisely here that the triumph of our theory appears: the slackened reins of government are immediately, by the law of life, caught up and gathered together by a new hand, because the blind might of the nation cannot for one single day exist without guidance, and the new authority merely fits into the place of the old already weakened by liberalism.

Then, there’s the same idea of law being a disguise for force:

Grant the late Casimir Périer ten years of life, of power and of ministry, and you will find a petty Richelieu without purple, a low-level tyrant, but surrounded by his guard, his flatterers, a court, courtiers, an entire constitutional Late Empire disguised by a mask of legality.

The Protocols:

In the beginnings of the structure of society they were subjected to brutal and blind force; afterwards — to Law, which is the same force, only disguised.

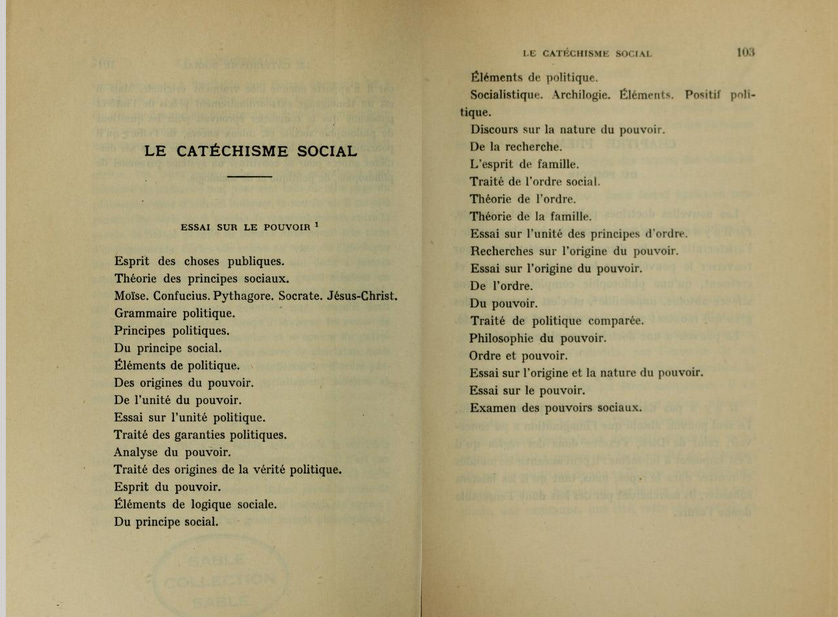

More interesting though was the beginning of the Essay on Power. One of the most distinctive and strange aspects of the Protocols must be the fact that each section starts with a long list of short phrases:

Off the top of my head, I can’t recall ever having seen something like this in another book. Except, that is, until I read the Essay on Power:

The longest sentence in both is 8 words. The Essay on Power has 35 sentences with an average of 3.88 words per sentence. The Protocols has 27 sentences with an average of 3.44 words per sentence. If you’re curious, here’s those sentences in English:

The Spirit of Public Affairs.

Theory of Social Principles.

Moses. Confucius. Pythagoras. Socrates. Jesus Christ.

Political Grammar.

Political Principles.

On the Social Principle.

Elements of Politics.

On the Origins of Power.

On the Unity of Power.

Essay on Political Unity.

Treatise on Political Guarantees.

Analysis of Power.

Treatise on the Origins of Political Truth.

The Spirit of Power.

Elements of Social Logic.

On the Social Principle.

Elements of Politics.

Socialistics. Archeology. Elements. Political Positivity.

Discourse on the Nature of Power.

On Research.

The Spirit of the Family.

Treatise on Social Order.

Theory of Order.

Theory of the Family.

Essay on the Unity of the Principles of Order.

An Inquiry into the Origin of Power.

Essay on the Origin of Power.

On Order.

On Power.

Treatise on Comparative Politics.

Philosophy of Power.

Order and Power.

Essay on the Origin and Nature of Power.

Essay on Power.

An Examination of Social Powers.

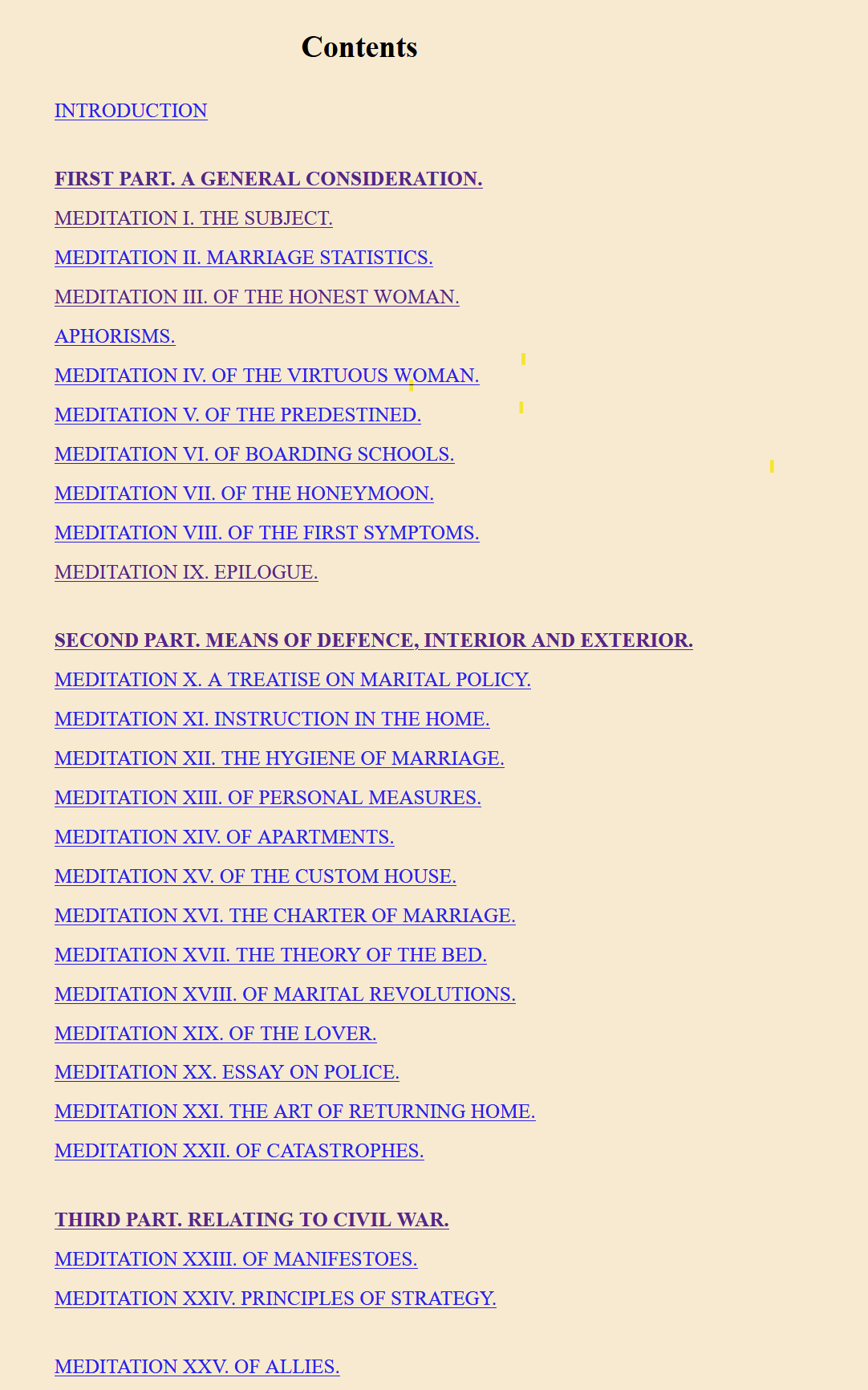

I’d be genuinely curious if anyone could find a single other work that begins like this. In comment #83 on my original article, I also noted the similarity in layout of Balzac’s Physiology of Marriage, one of his few non-fictional (mostly) works, with the Protocols.

In comment #135, I asked ChatGPT for ten other French political non-fiction works from 1800-1850 and noted that none of those seemed to use this layout. After checking those same ten (actually nine) works again I didn’t see anything even remotely close to the strange opening of the Essay on Power and the Protocols.

In the commentary on this essay, the author attempts to figure out when the Essay on Power was written. Lovenjoul, who collected the manuscript, says it was written in 1848. The author disagrees though and puts forward some convincing evidence that it was actually probably written around 1841. One of the arguments he made stuck out to me though for other reasons:

As for the Revolution of 1848, it had, as we have just said, made a profound impression on Balzac’s mind, and it would be truly strange if nothing of it had been reflected in these notes to the Social Catechism, which are, on the contrary, remarkably serene, without the slightest allusion to the political turmoil that France was experiencing at that time. To what date, then, should we place the composition of these notes?

As the author says, the 1848 revolution made a profound impression on Balzac’s mind, so it would be strange for it to be so little reflected in this work. For the same reason, I find it strange that Balzac wrote almost nothing, that we know of, on the 1848 revolution that he experienced so intimately. Shortly after writing my first article, I discovered one of the few things that he did write on the revolution but never published, a short document called the Letter on Labor, which was discovered and published in the 20th century. In it, I noticed probably more parallels to the Protocols than in any of his other works on a per-word basis.

Balzac, in the Letter on Labor, begins with describing the press as the power behind the government and refers to the new power as a terrorist:

A newspaper, which helped create the Government, suddenly becomes a plagiarist of intimidation. It declares anyone who would propose a form of government other than the Republic a traitor to the country. This newspaper thus grants us the freedom to do whatever it pleases. After monarchical arbitrariness, we have terrorist arbitrariness.

The Protocols:

We must compel the governments of the goyim to take action in the direction favoured by our widely-conceived plan, already approaching the desired consummation, by what we shall represent as public opinion, secretly prompted by us through the means of that so-called “Great Power” — the Press, which, with a few exceptions that may be disregarded, is already entirely in our hands.

In a word, to sum up our system of keeping the governments of the goyim in Europe in check, we shall show our strength to one of them by terrorist attempts…

Balzac, Letter on Labor:

The words “organization of labor” mean a coalition of workers, and the word “worker” has only one translation: “manual laborer.” All other forms of work have been magically eliminated: intellectual work, managerial work, inventive work, the work of travelers, the work of scholars, and so on…

As soon as wages are doubled, the prices of consumer goods will follow suit…Therefore, the worker, with his ten hours of work and higher daily wage, will find himself in the same situation as before. He will eat and consume his entire wage. There will be no improvement in his condition…

At one point, all wages doubled due to the reduction in working hours; and, because of the increased cost per day’s work, production necessarily decreases…

In those few paragraphs, Balzac discusses the how the raising of wages will raise prices, resulting in no gain for workers, how this will undermine production, and how educated workers are being disenfranchised. Now, the Protocols:

We shall raise the rate of wages which, however, will not bring any advantage to the workers, for at the same time, we shall produce a rise in prices of the first necessaries of life, alleging that it arises from the decline of agriculture and cattle breeding: we shall further undermine artfully and deeply sources of production, by accustoming the workers to anarchy and to drunkenness and side by side therewith taking all measure to extirpate from the face of the earth all the educated forces of the GOYIM.

Balzac, Letter on Labor:

This is the last experiment; the State entered into it as a protector. Today, it rushes in as a doctor. Well, it is in the process of killing the patient.

The Protocols:

These institutions have divided up among themselves all the functions of government — administrative, legislative, executive, wherefore they have come to operate as do the organs in the human body. If we injure one part in the machinery of State, the State falls sick, like a human body, and will die.

Balzac, Letter on Labor:

The Provisional Government…requests at the same time time the consecration of the Republic to a National Assembly, in terms and with means which leave no doubt about the universal vote…

If the right holds the majority, if it has six hundred votes out of nine hundred, well, what will become of it in the face of a minority to which the February Revolution gives the right to call upon the masses for support?

The Protocols:

To secure this we must have everybody vote without distinction of classes and qualifications, in order to establish an absolute majority, which cannot be got from the educated propertied classes.

Balzac, Letter on Labor:

It is, finally, tyranny, in the name of a specious theory, false in application.

The Protocols:

We have fooled, bemused and corrupted the youth of the goyim by rearing them in principles and theories which are known to us to be false although it is by us that they have been inculcated.

The following isn’t really a parallel, but shows that Jews were on his mind during the revolution:

In the Middle Ages, did the most cruel tortures wrest two deniers from the Jews’ treasures? Louis XIV, in 1707, could he be given to Money? When, prostituting himself to Samuel Bernard, and imposing the vanity of this Jew…

At the end of the document, Balzac says that he’s planning to write another one with a focus on taxation, but it was never written or at least has never been found. I find it interesting that there’s a lot of discussion of niche tax issues in the Protocols, especially related to literature:

We turn to the periodical press. We shall impose on it, as on all printed matter, stamp taxes per sheet and deposits of caution-money, and books of less than 30 sheets will pay double… The tax will bring vapid literary ambitions within bounds and the liability to penalties will make literary men dependent upon us.

Purchase, receipt of money or inheritance will be subject to the payment of a stamp progressive tax. Any transfer of property, whether money or other, without evidence of payment of this tax which will be strictly registered by names, will render the former holder liable to pay interest on the tax from the moment of transfer of these sums up to the discovery of his evasion of declaration of the transfer... Just strike an estimate of how many times such taxes as these will cover the revenue of the goyim States.

Possibly, he threw what he had for the letter on tax into the Protocols.

While the evidence presented so far seems very suggestive, it would be nice if a computer analysis could add a more objective element. If our hypothesis is correct, we would probably expect Balzac’s Letter on Labor to most closely match the Protocols stylistically, given that he likely would have written the latter shortly afterwards.

Much work has been put into the field of stylometry due to its numerous practical applications, especially finding criminals on the basis of anonymous writings. It is also very important for historical studies though, such as finding out which plays should be attributed to Shakespeare or who wrote certain parts of the Federalist Papers.

Anyone who looks into stylometry will quickly find that the most widely used program is R-stylo, which has become the de facto standard. R-stylo was developed by Prof. Maciej Eder, a professor of linguistics at the Institute of Polish Language, and it has become the backbone of the Computational Stylistics Group.

One of the reasons that R-stylo is so popular is because it makes it so easy to run analyses of the most frequent words in a document corpus and then to compare the individual documents to each other. This method of comparing how often works use common words is currently the standard test for authorship attribution. It is considered especially effective because authors tend to select these common words unconsciously, meaning that their unique style tends to shine through regardless of changes in topic. In an article for The Irish Times, Dr. James O’Sullivan, a lecturer in the Department of Digital Humanities at University College Cork, and Rachel McCarthy, a student of his, used this method to seemingly confirm Emily Brontë as the writer of Wuthering Heights. Summary below:

That is precisely what our recent study, published in Digital Scholarship in the Humanities (Oxford University Press), sets out to accomplish. Armed with stylometry we ask, who wrote Wuthering Heights? Stylometry is based on a simple premise: by counting the frequency of words in a text, you can form a profile of how an author writes, and then use that quantitative measure to forensically test things like authorship, influence, genre, or anything that might be related to how something is written. Using individual writing samples and some very clever tools developed by the Computational Stylistics Group, we algorithmically formed quantitative authorial fingerprints for each of the Brontë siblings, and then used those signatures to conduct a stylometric analysis of Wuthering Heights to see, statistically speaking, who is the novel’s most likely author. The same technique has been used to do authorship attribution tests of works by major literary figures like James Patterson, JK Rowling and Harper Lee.

There is the question though of how many of the most frequent words in a text corpus should be counted when performing this analysis. Using too few would not provide much differentiation, where as too many might start to include words that say more about the topic than the author’s style. This article in Programming Historian sheds some light on the matter:

No matter which stylometric method we use, the choice of

n, the number of words to take into consideration, is something of a dark art. In the literature surveyed by Stamatatos1 scholars have suggested between 100 and 1,000 of the most common words; one project even used every word that appeared in the corpus at least twice. As a guideline, the larger the corpus, the larger the number of words that can be used as features without running the risk of giving undue importance to a word that occurs only a handful of times.

This range of 100-1000 is a nice sweet spot, and in a YouTube tutorial (14:55), Prof. Eder also recommends analyzing this range, preferably at intervals of 100.

In a comment on my last article on this topic, I asked ChatGPT for ten French political non-fiction works written between 1800 and 1850 for the sake of making a comparison with the Protocols. While the Protocols may technically be “fictional,” there is no dialogue, imagery, or any of the usual hallmarks of fiction, and so structurally it is much closer to non-fiction, especially political philosophy.

One of the links is duplicated, so there’s actually nine works in my comment. The works are:

Benjamin Constant - Principes de politique (1806)

Germaine de Stael - Considerations on the Main Events of the French Revolution (1815)*

Francois Guizot - General History of Civilization in Europe (1828)

Joseph de Maistre - Du Pape (1819)

Louis de Bonald - Analytical Essay on the Natural Laws of Social Order: or, On Power, the Minister, and the Subject in Society (1800)

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon - On the Reorganization of European Society (1814)

Charles Fourier - The New Industrial and Societal World (1829)

Pierre Leroux - Legality (1848)

Jean-Baptiste Say - Treatise on Political Economy (1803)

*I could only find part four online in the original French for this work, so that’s what I use.

I figured these nine works plus Balzac’s Letter on Labor, Modern Government, and Essay on Power would be a good starting point for building a body of works that could be compared to the Protocols. It would be nice if Balzac had written some lengthier non-fiction works for comparison, but even mostly non-fictional works such as The Physiology of Marriage and The Journalists frequently transition into fiction and therefore aren’t especially helpful for our purposes.

Pretty straightforward, right? Well, not exactly. For the Protocols, we have no copy of the French original, and so we are forced to use a translation, which may not perfectly represent the original style. I considered a few ways to best account for this. Running everything in English would obviously not be very satisfactory, given that we’d be comparing a French > Russian > English document to French > English documents. I considered running everything in French, but comparing original French to a French > Russian > French document also seemed unlikely to be effective.

Finally, I decided the best option would be to run an original Russian copy of the Protocols against Russian translations (via Google translate) of the other works from the original French. This would be French > Russian compared to French > Russian and it would also preserve the Protocols as close to the original as possible, avoiding a double layer of translation. Thankfully, Eder mentions in the video (5:10) that the program works for Cyrillic as well.

First, let’s test how well this French > Russian strategy works without including Balzac’s non-fiction yet. I asked ChatGPT to give me another work written by each of the first three authors on the list: Constant, de Stael, and Guizot, so that I could see how well it could match these works to the others by the same author.

I couldn’t find the exact work History of the English Revolution online in French, but I did find Guizot’s Why was the English Revolution Successful?: A Discourse on the History of the English Revolution (1850) that was published shortly afterwards. Constant’s Spirit Conquest was written eight years after his work on our original list, de Stael’s was written 17 years later, and Guizot’s 22 years later, so these works should not be too similar.

Let’s also beef our corpus up a bit more. I noticed that the original list skewed towards the first half of the 1800-1850 period, so I asked ChatGPT for an 1850’s work and threw in Alexis de Tocqueville — L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution (1856). I also threw in Maurice Joly’s The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu (1864) given its relevance to the Protocols. I then decided that I should include some authors who could be reasonable alternative candidates. In comment #272 of my original article, Ron Unz pointed out that the Protocols was probably inspired by the 1844 work Coningsby, so I asked ChatGPT for a list of ten political non-fiction works written between 1844 and 1860 from a right wing perspective.

This list only ended up providing four works to use, since two are translations from Spanish, two don’t actually specify a work, one is a repeat of Bonald, and Saint-Bonnet is on there twice. So, I added:

Antoine Blanc de Saint-Bonnet — De la Restauration française : mémoire présenté au clergé et à l’aristocratie (1851)

Louis Veuillot — L’Illusion libérale (1848)

François-René de Chateaubriand — Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe (vols. published 1848–1850)

Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly — Du dandysme et de George Brummell (1845)

I also decided that some fiction should be included for comparison. I added Balzac’s Lost Illusions (part three, which was all I could find in the original French), Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, Sue’s The Mysteries of Paris, and Charles Rabou’s Le Capitaine Lambert. Rabou was hired by Madame Hanska to ghost write Balzac’s unfinished works after he died, so I figured he may be relevant too.

Before running this analysis, I did some minor cleanup of the documents, mainly removing prefaces or introductions that weren’t written by the author and other text not part of the works. All of the text files that I used in this analysis can be found here.

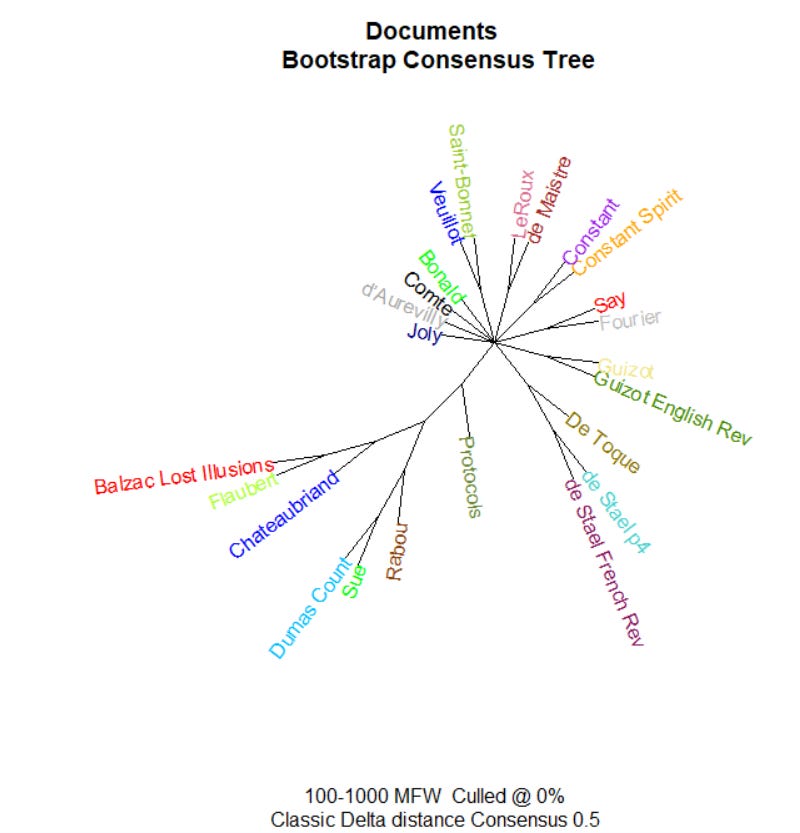

Now, let’s see if R-stylo can correctly match the two French > Russian works by Constant, de Stael, and Guizot together with each other. Eder recommends running a consensus tree analysis which averages the results of 100-1000 MFW (most frequent words) at intervals of 100. It then groups them together based on similarity and outputs a nice graph. Here’s the results:

Very impressive, three for three. We can also see that the fiction clusters together, it appears that the stylistic differences of fiction and non-fiction are unsurprisingly very significant. Also notice how none of these writers strongly match the Protocols.

Now, when I ran this same test with Balzac’s Letter on Labor, it easily matched the Protocols. Unfortunately, I soon discovered that the short length of the Letter on Labor is a major factor, and the consensus tree has a tendency to match together outliers even if they are not all that similar in the raw data. So, to get a more genuine result, it is better to dive into the raw data and to account for the length discrepancy.

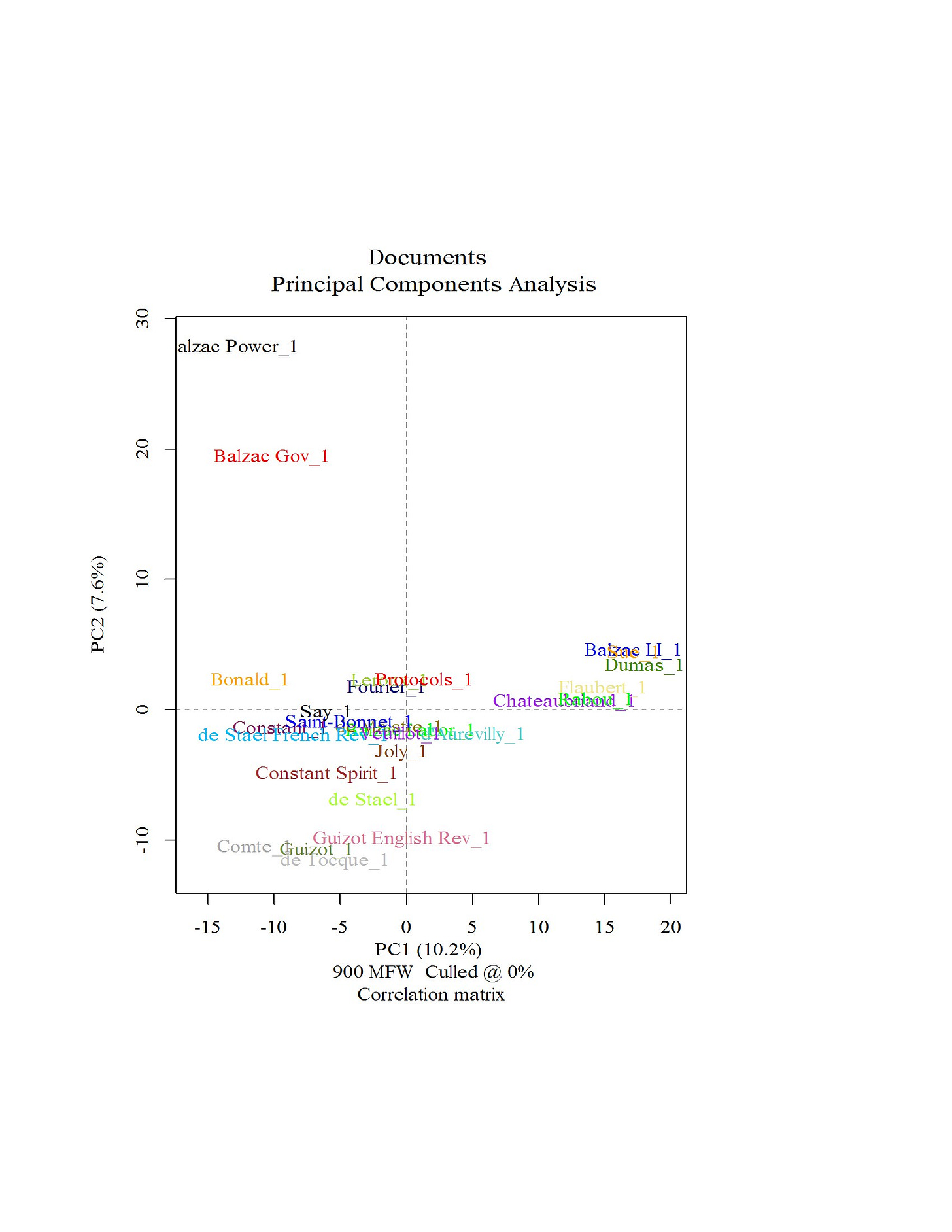

To do that, R-stylo recommends that we “sample” each work. We can set it to take a random sample of each work that is the exact length of Balzac’s Letter on Labor, thereby equalizing the length for all works. Then, to get more exposure to the raw data, Eder recommends that we use the Principal Components Analysis graph (13:10).

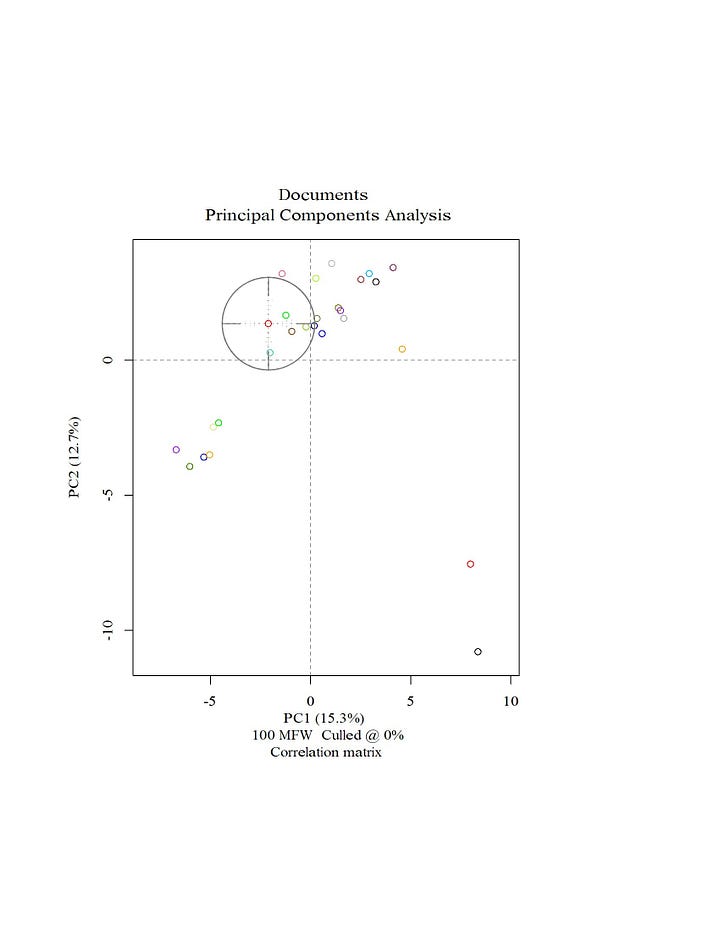

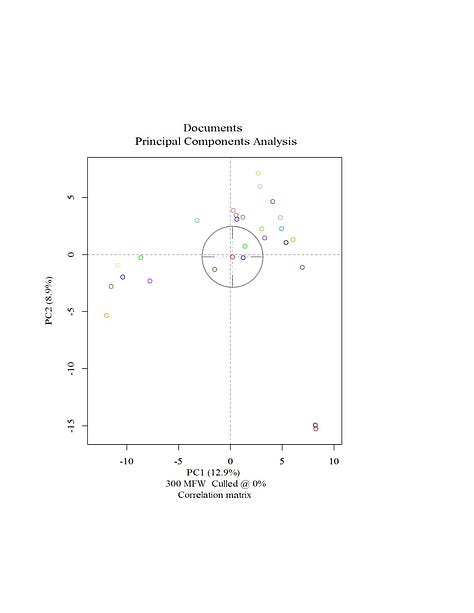

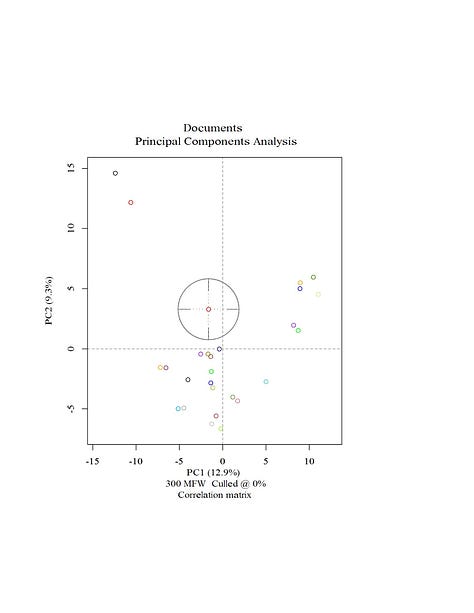

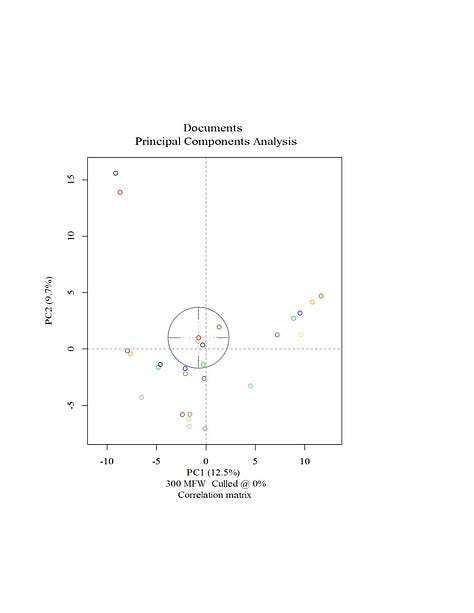

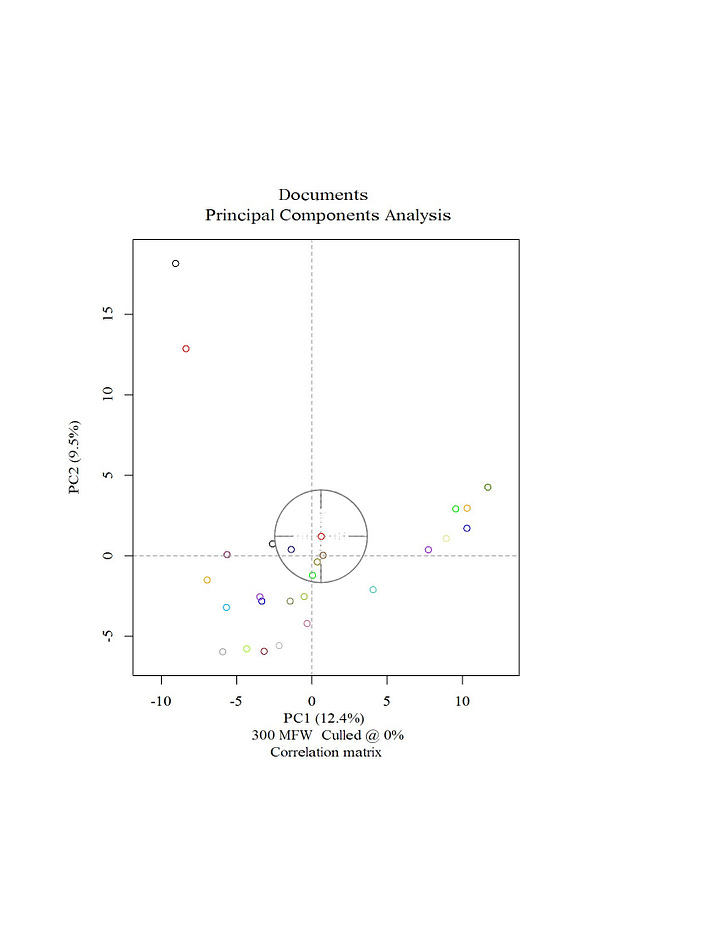

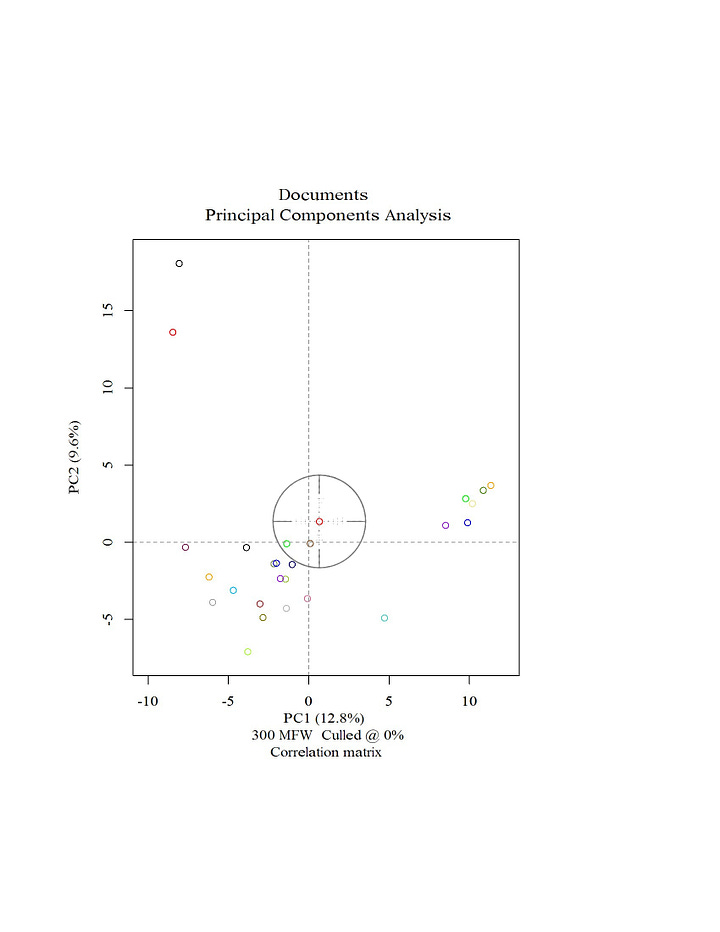

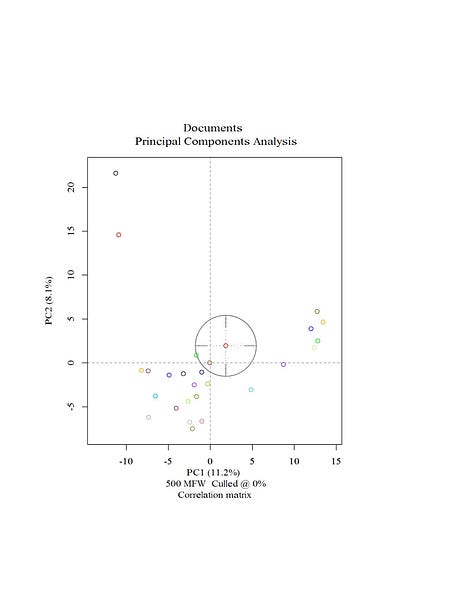

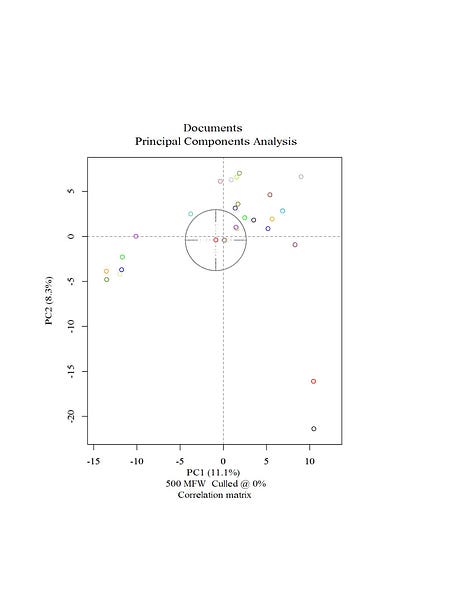

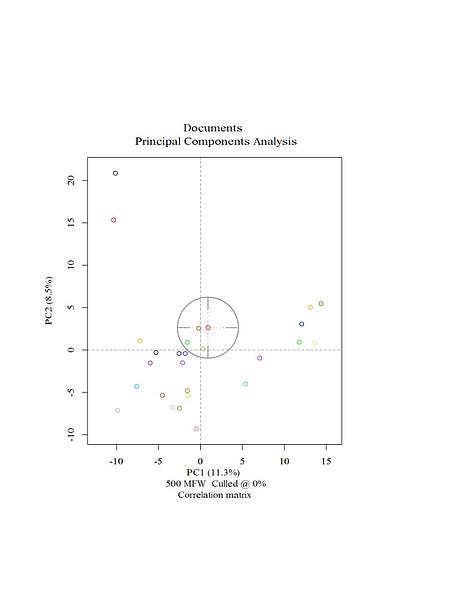

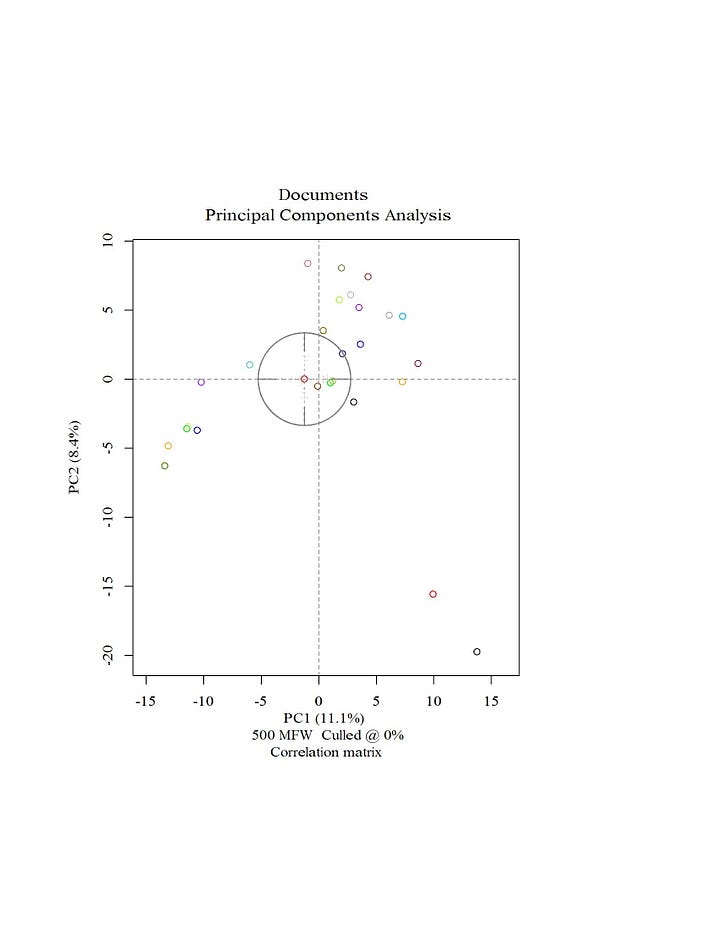

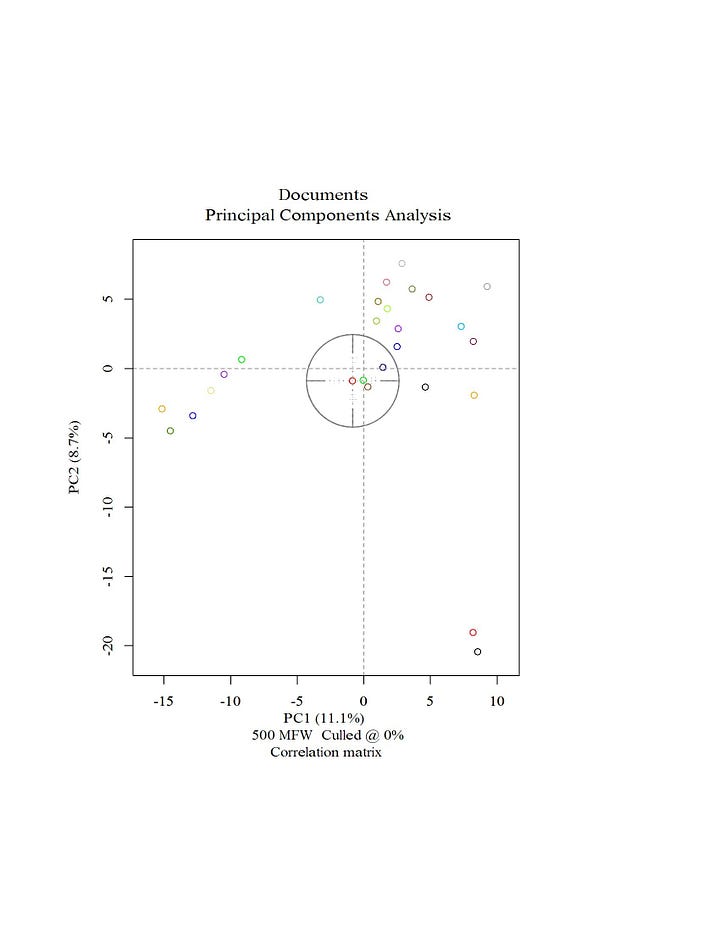

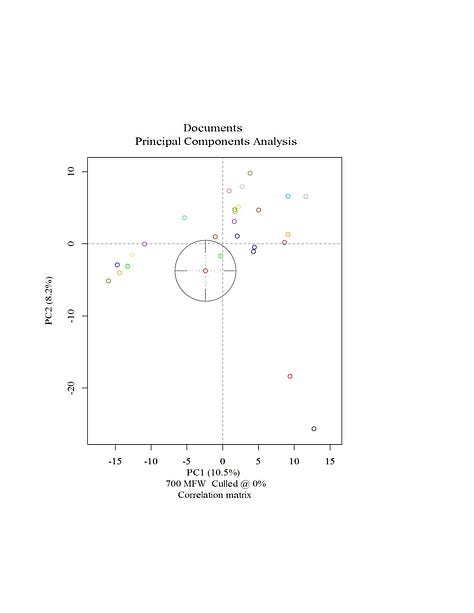

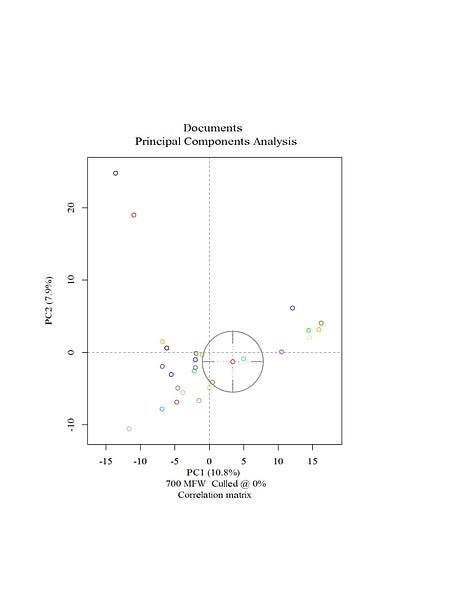

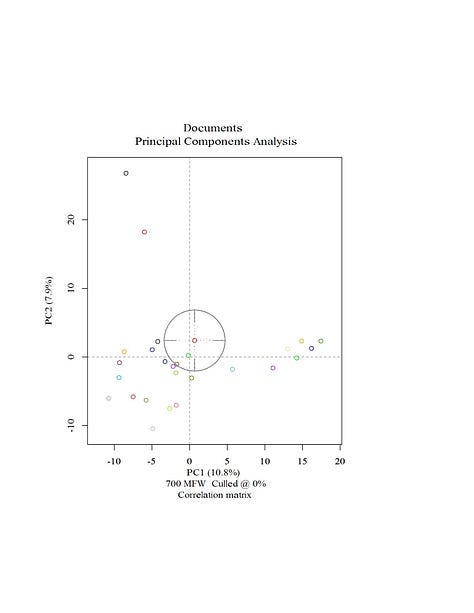

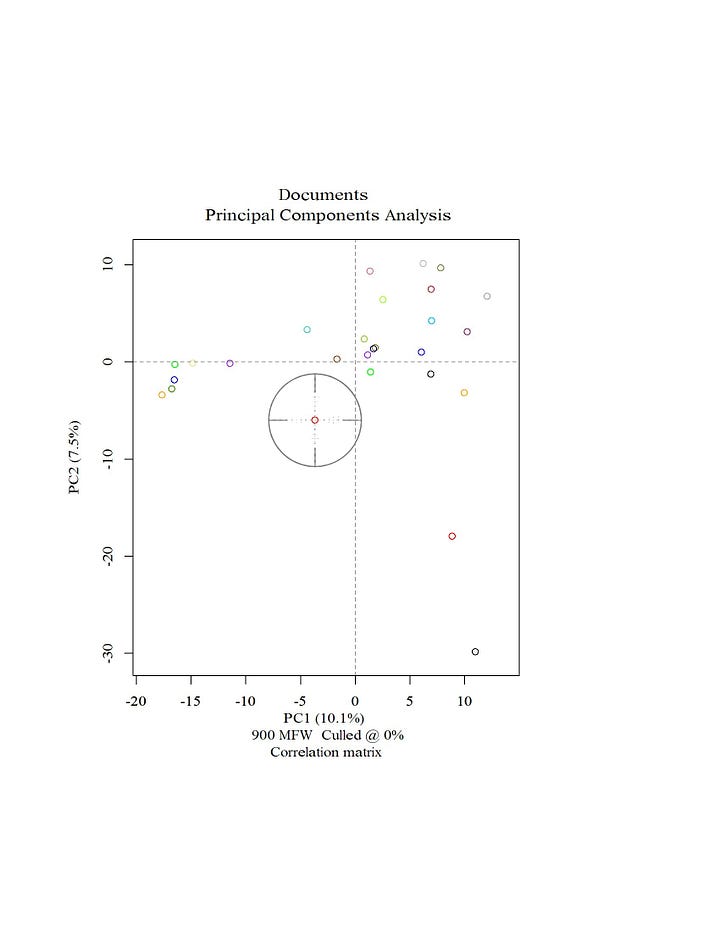

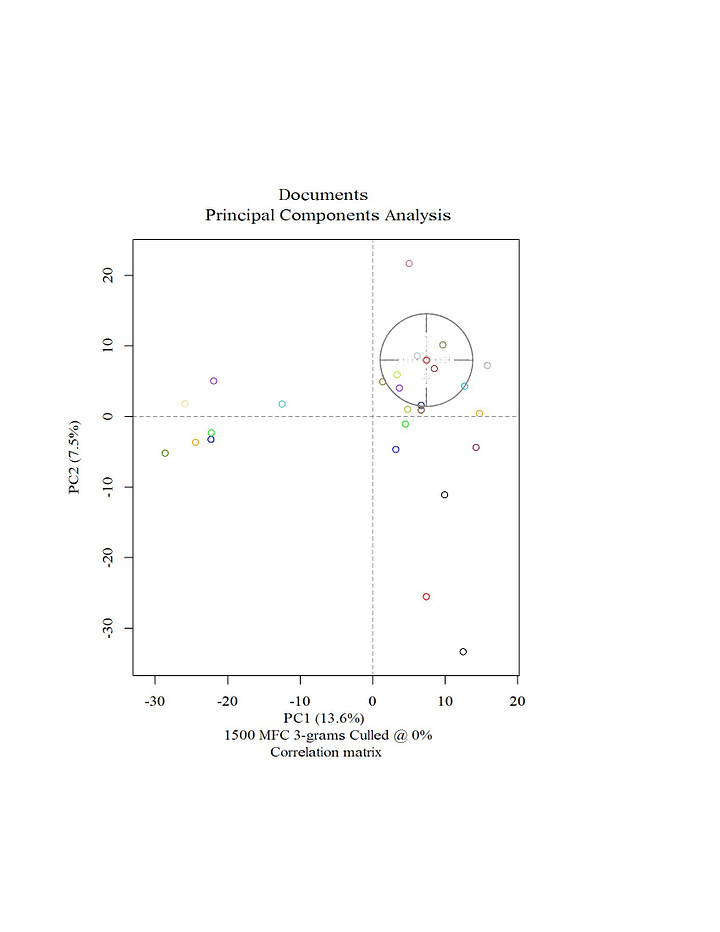

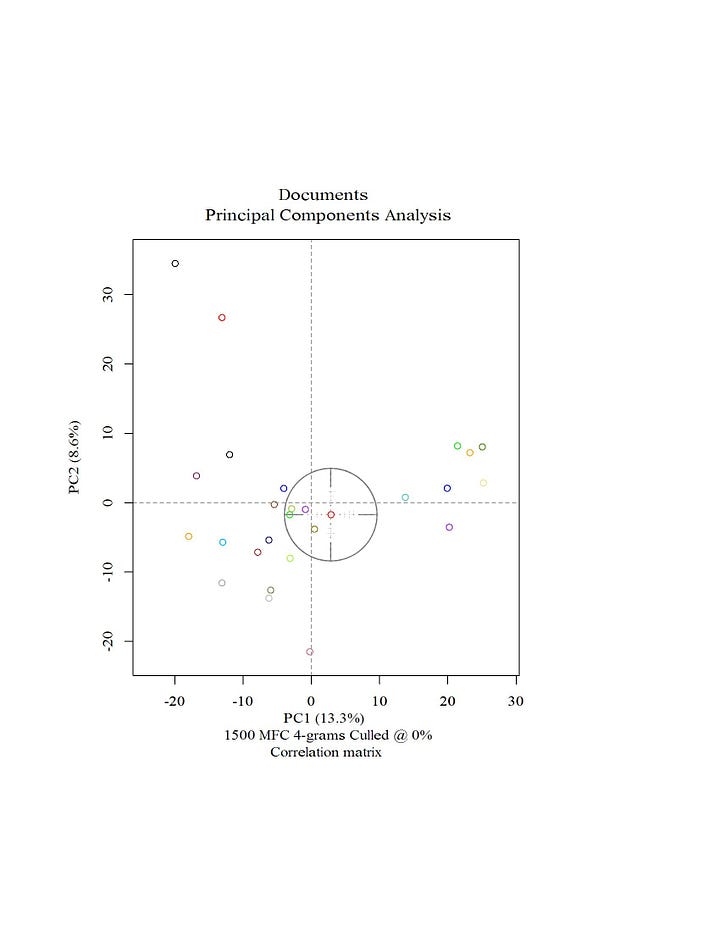

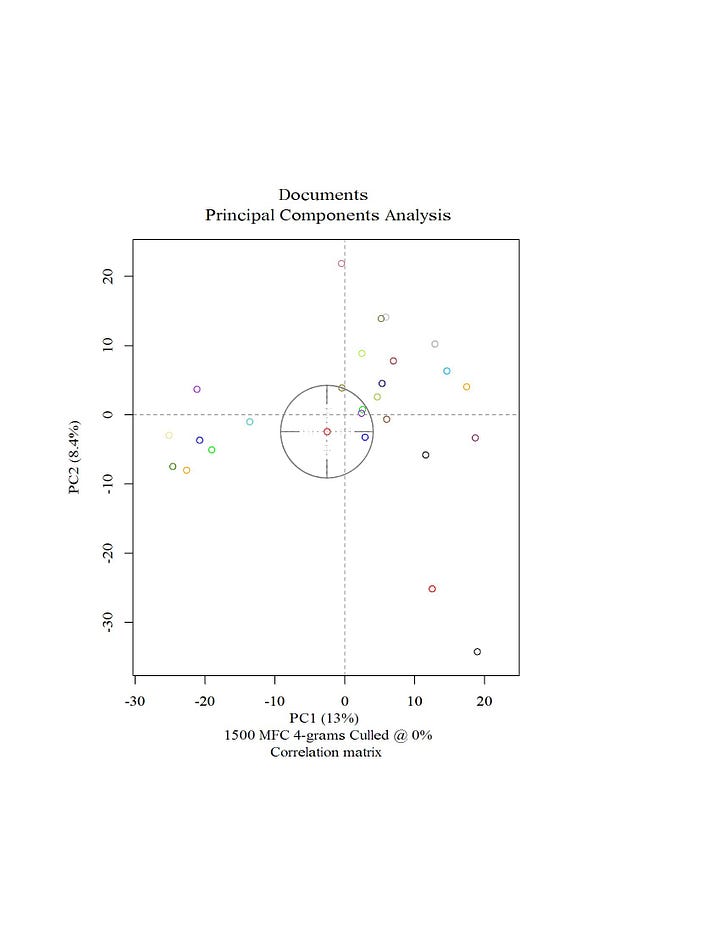

We can’t run a consensus analysis with the PCA graph, so let’s run five tests at each of 100, 300, 500, 700 and 900 MFW. The Protocols is represented by the red dot, and I have overlain a target on to it. The neon green in the non-fiction cluster is Balzac’s Letter on Labor. This analysis was easiest to run with dots, and I’ll summarize the results at the end if you don’t want to look at 25 graphs, but I’ll also post one example that shows the titles and color-coding for all of them, if you’re curious:

Now, here’s the results

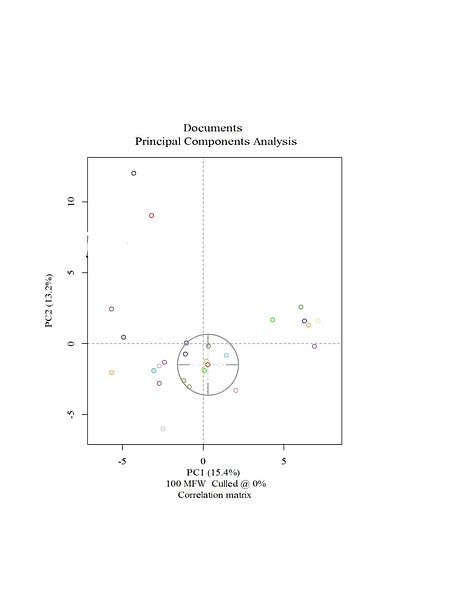

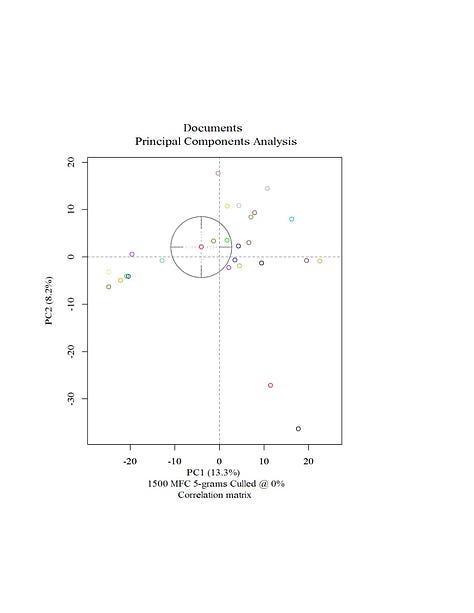

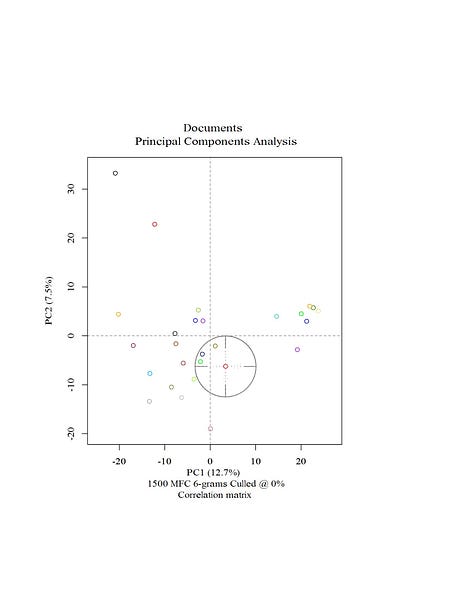

100 MFW:

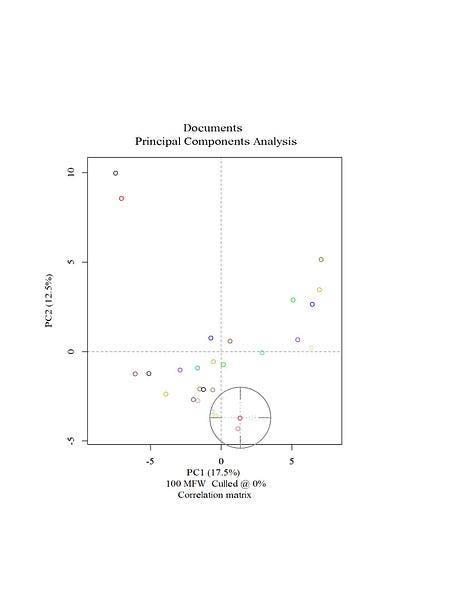

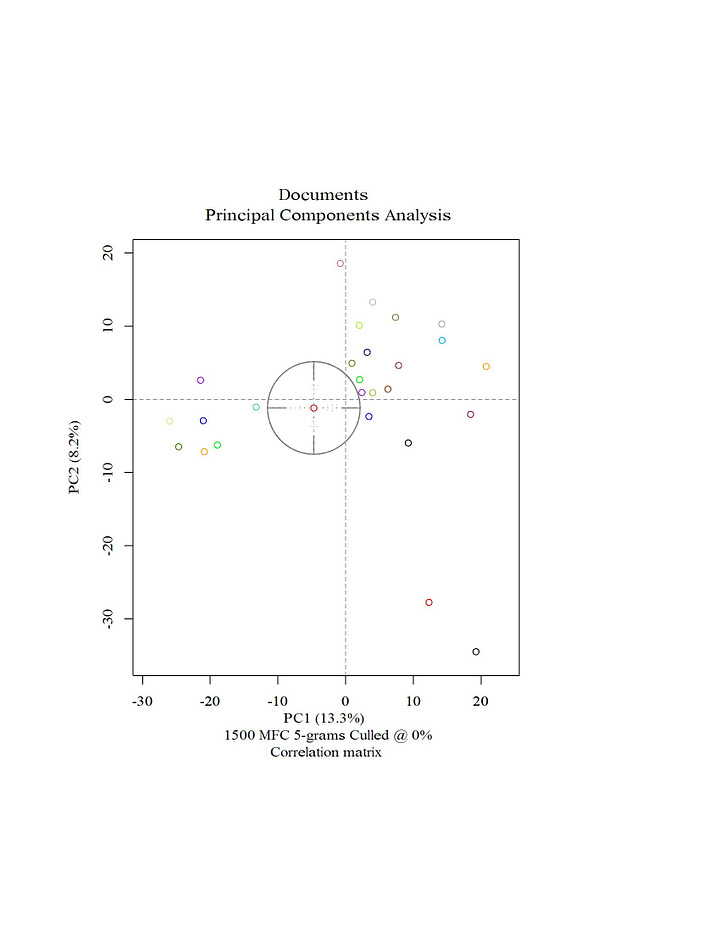

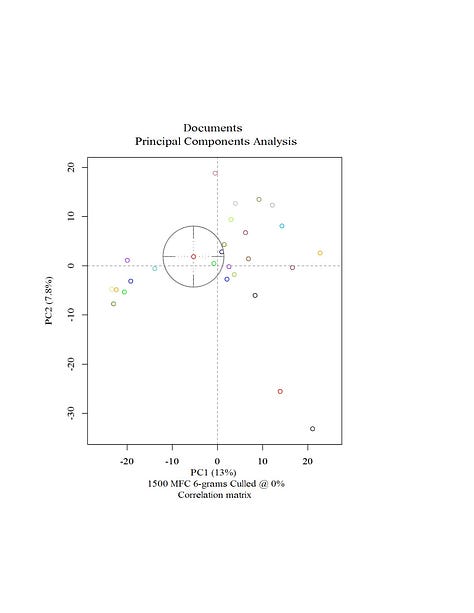

300 MFW:

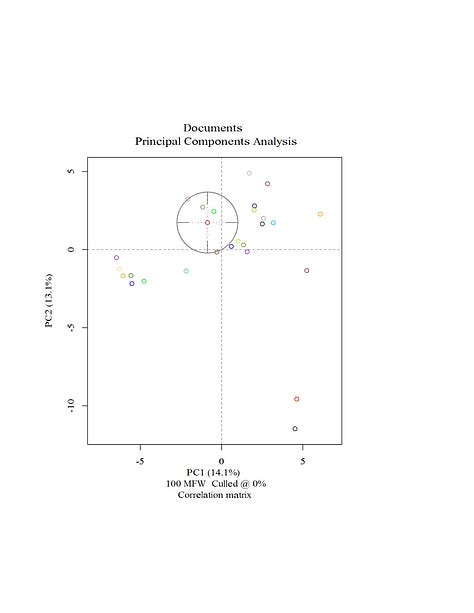

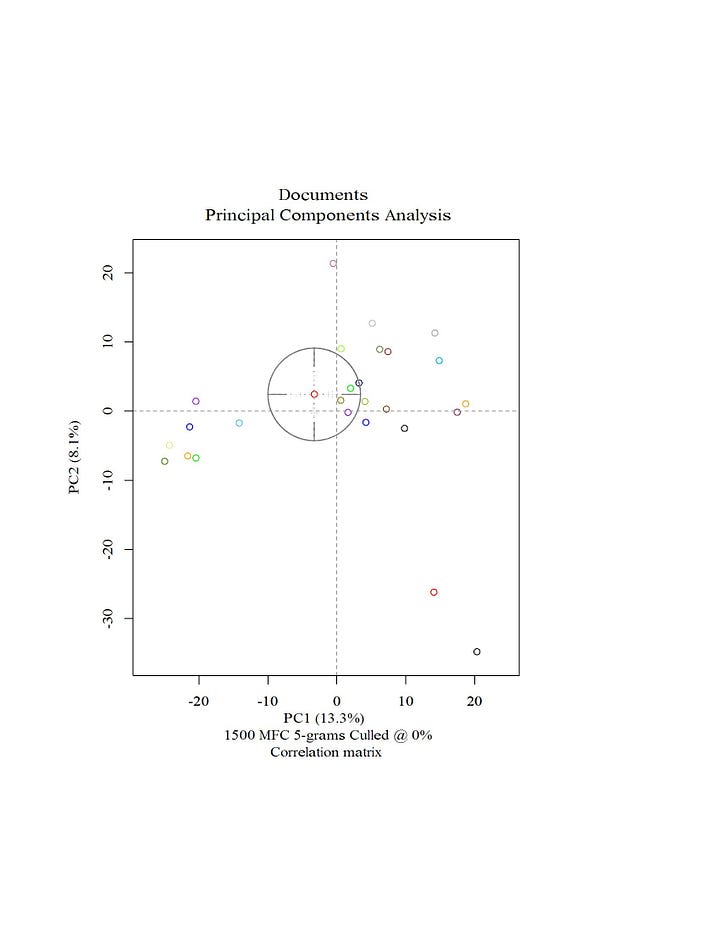

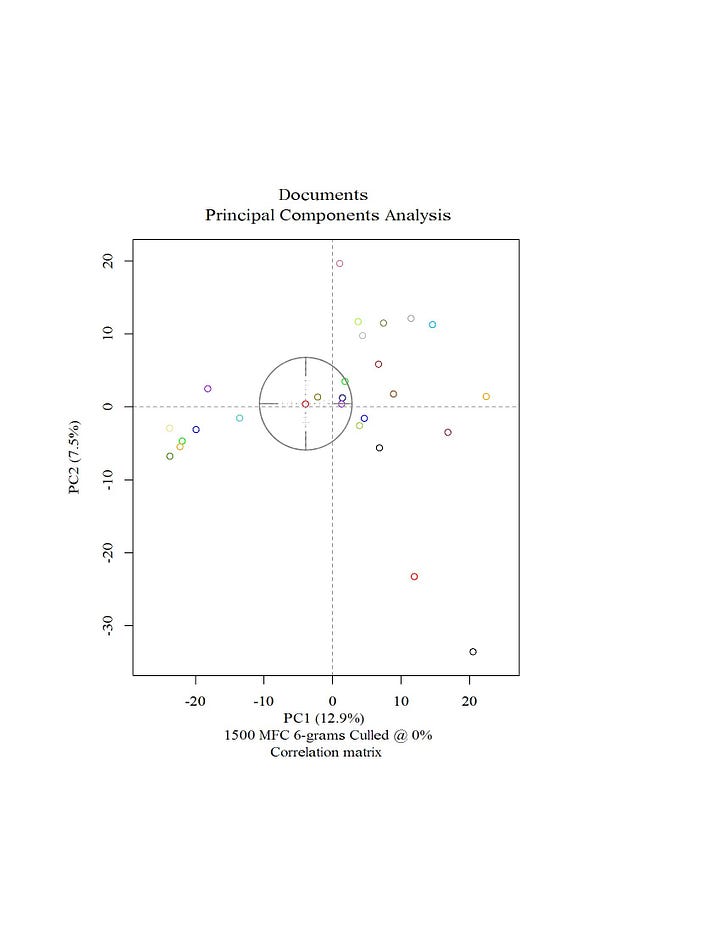

500 MFW:

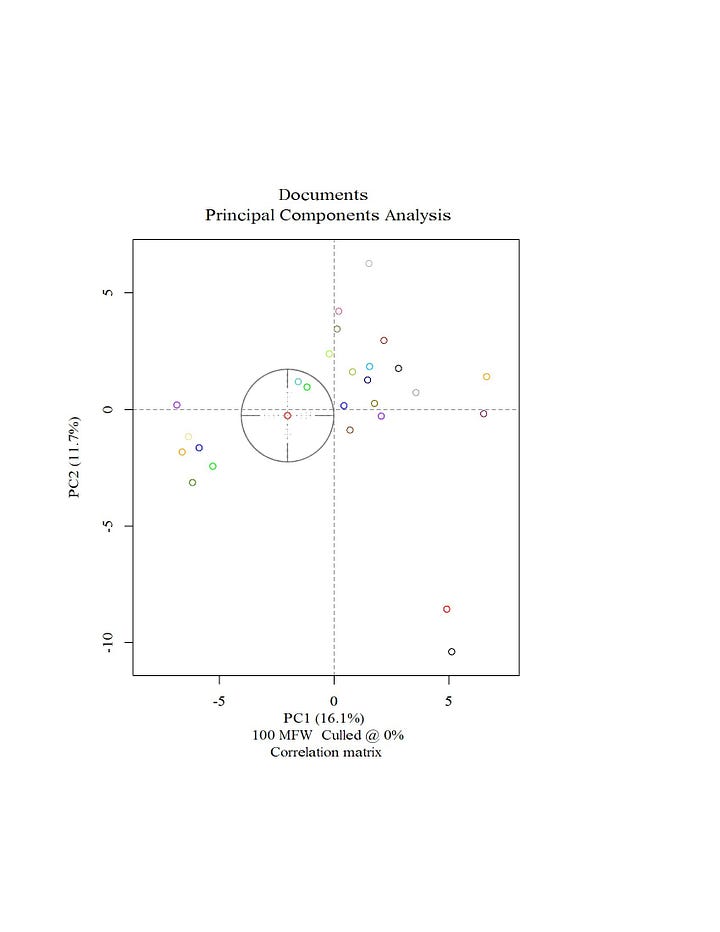

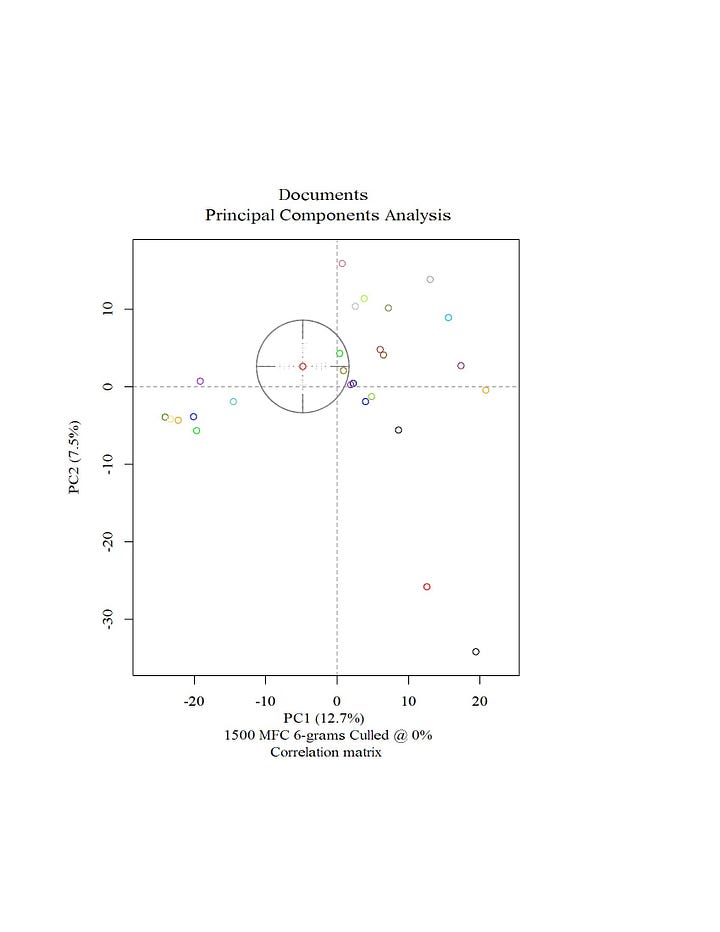

700 MFW:

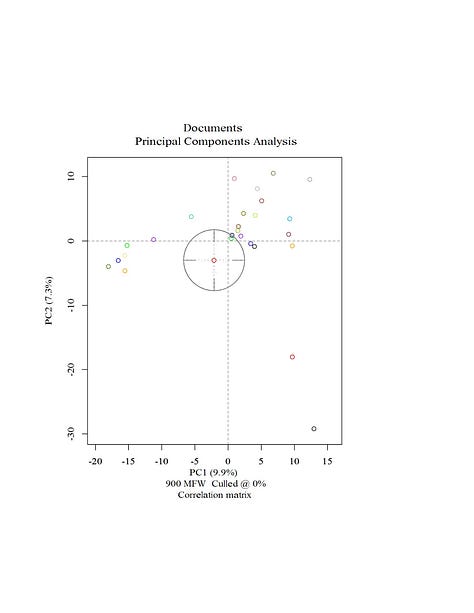

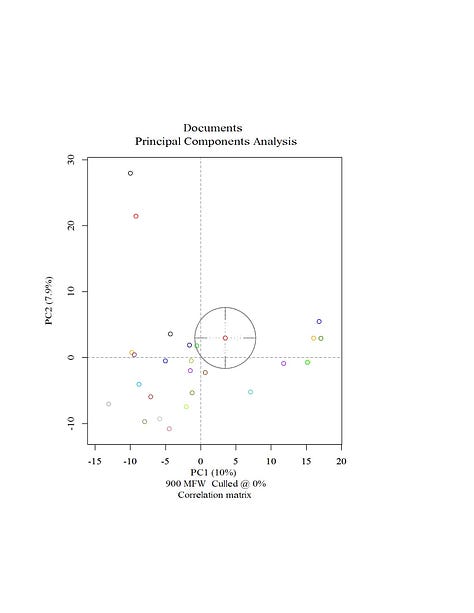

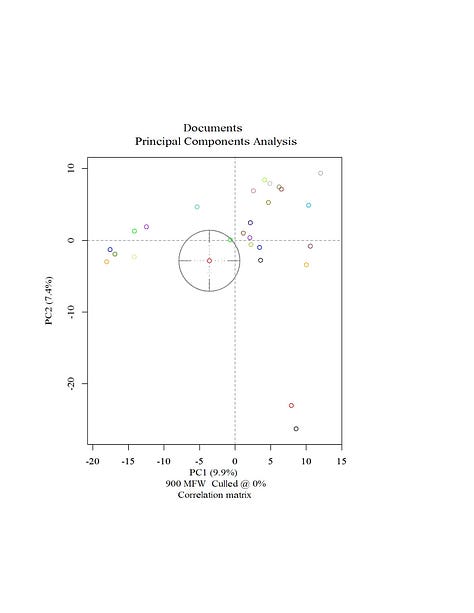

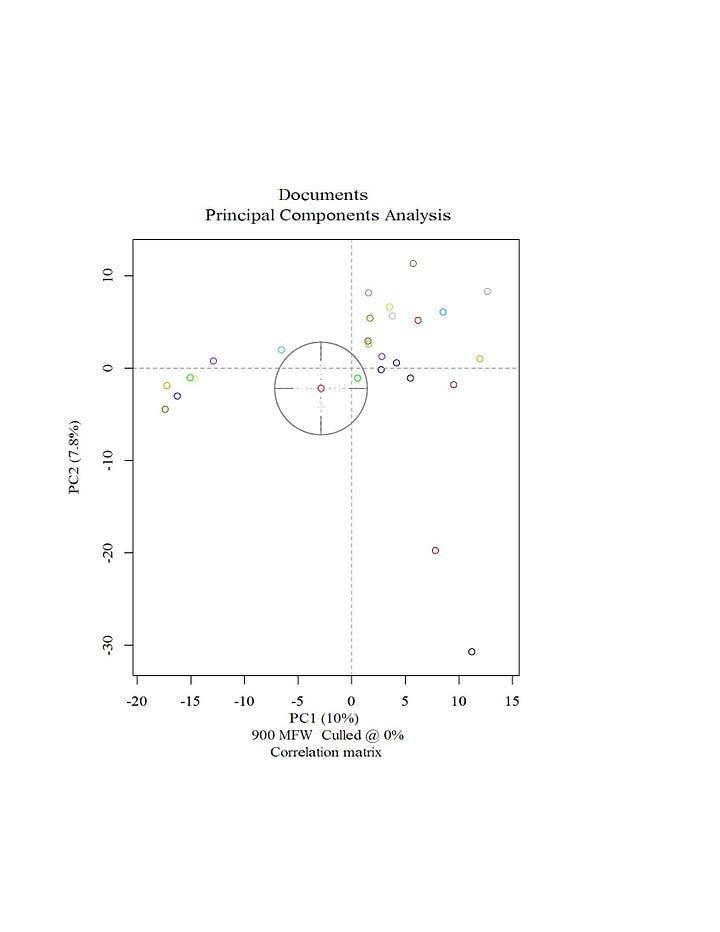

900 MFW:

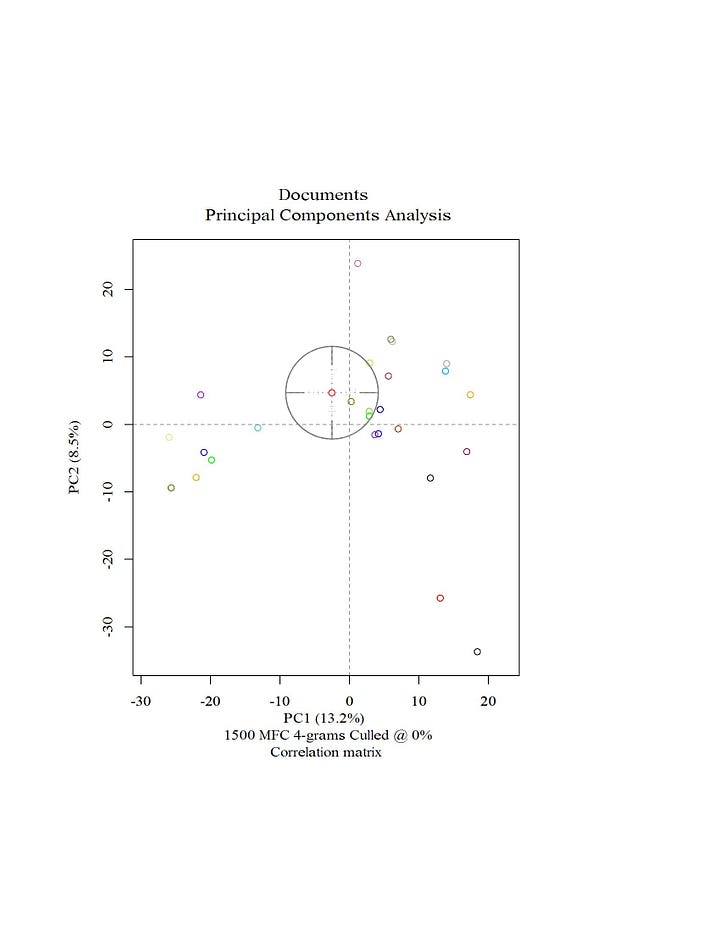

There doesn’t seem to be a way in R-stylo to get a direct measurement of the distance, so as a work-around, I counted up how many times each work landed inside the target bubble. (Note: I define any that touch the edge of the bubble as “inside”). Here are the results of that:

Totals:

Balzac Labor: 19

Joly: 15

Fourier: 9

Leroux: 8

d’Aurevilly: 3

Guizot: 3

Guizot English: 2

de Maistre: 2

de Tocqueville: 1

If you did look through the graphs, you saw that the Letter on Labor was frequently right next to the Protocols, and almost always in the general vicinity. The final tally reflects that. It should probably be unsurprising that Joly comes in second place, given that he likely extensively plagiarized the Protocols. No one else is really all that close. It’s also interesting that none of our possible rivals, St. Bonnet, Veuillot, Chateaubriand or d’Aurevilly even register much at all.

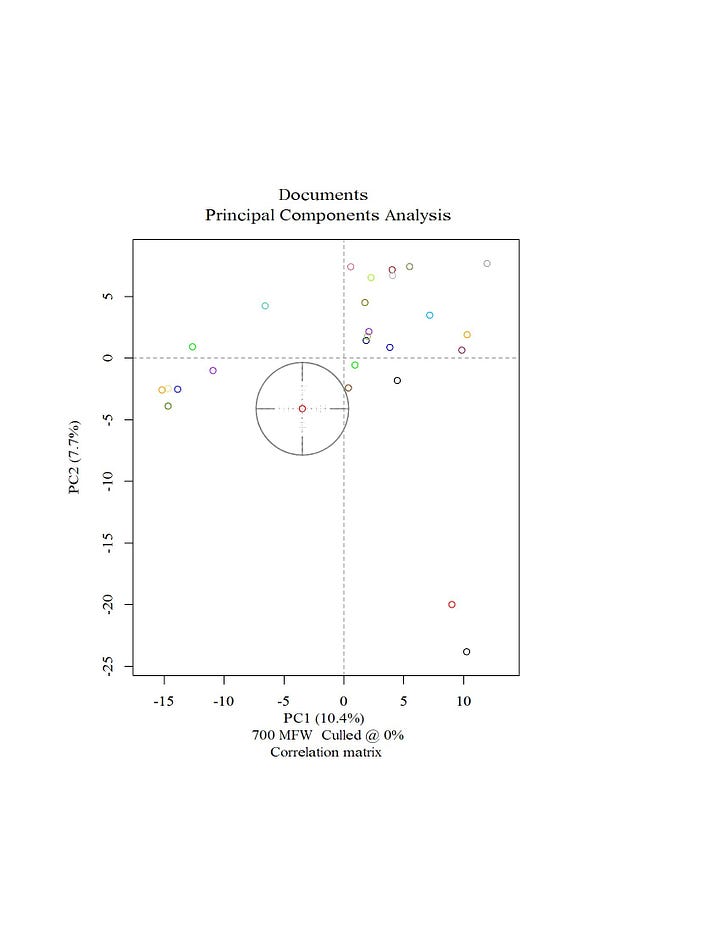

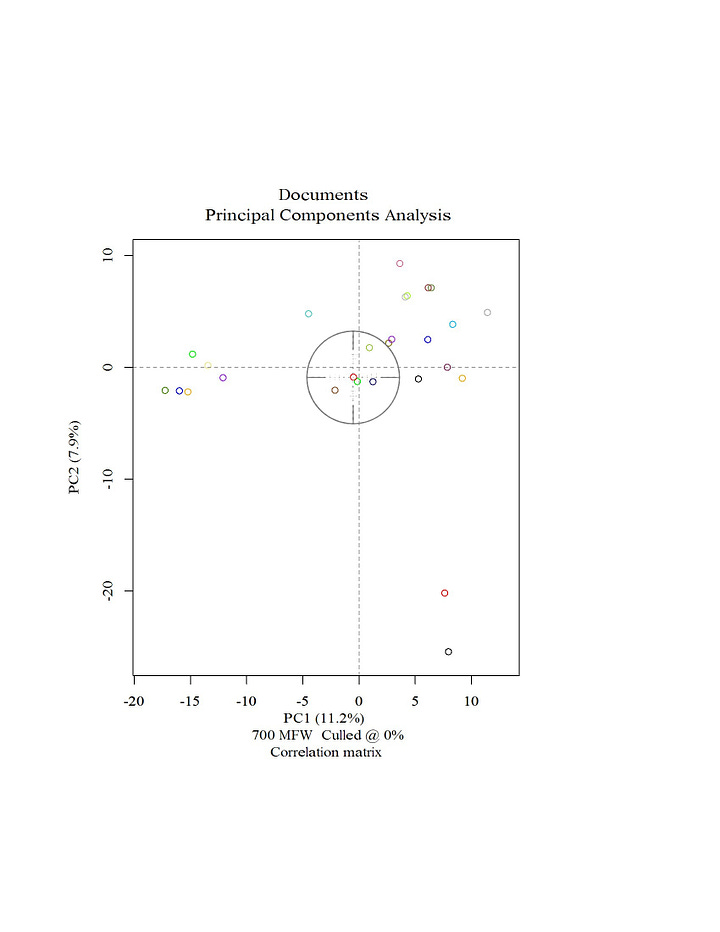

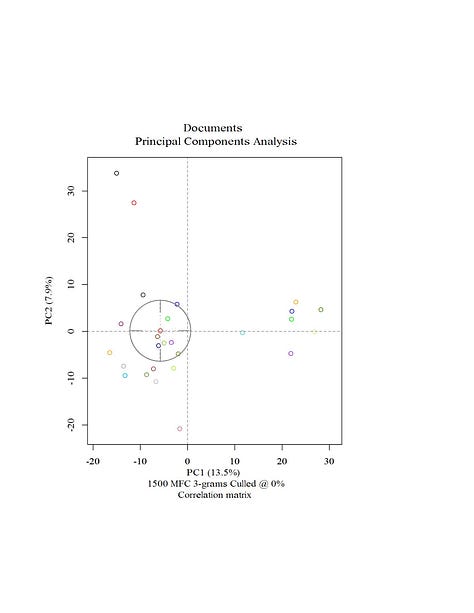

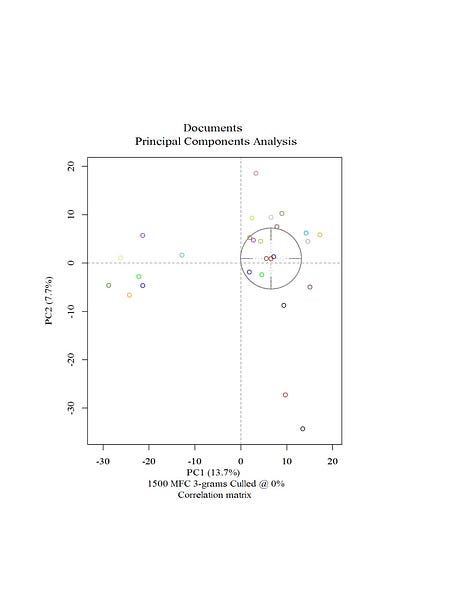

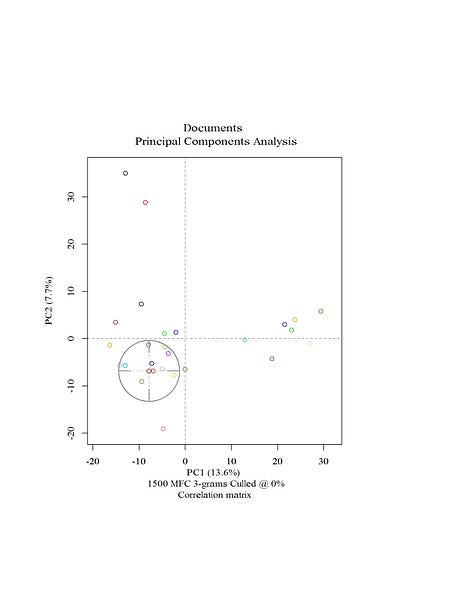

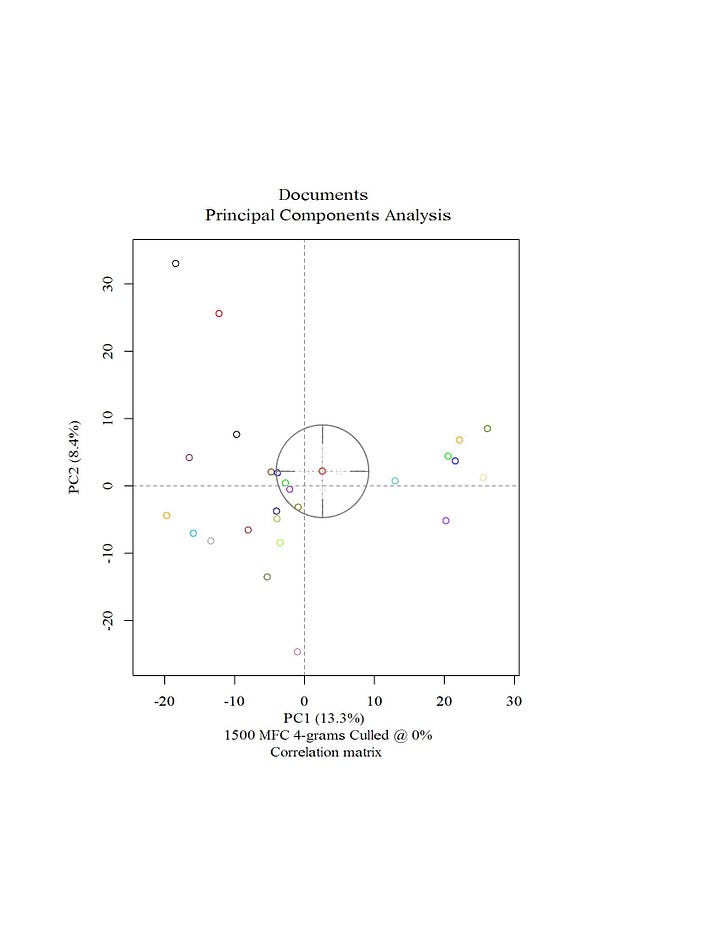

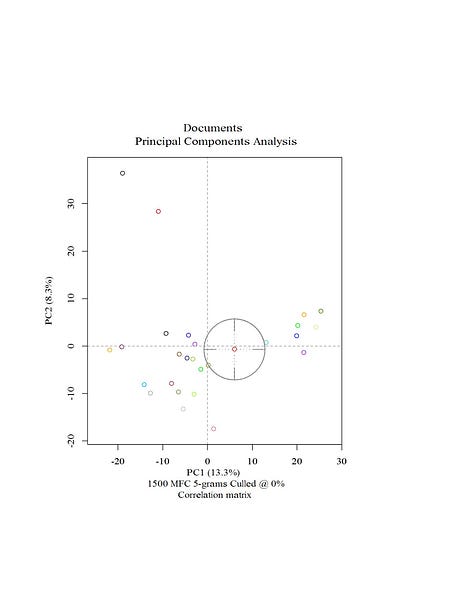

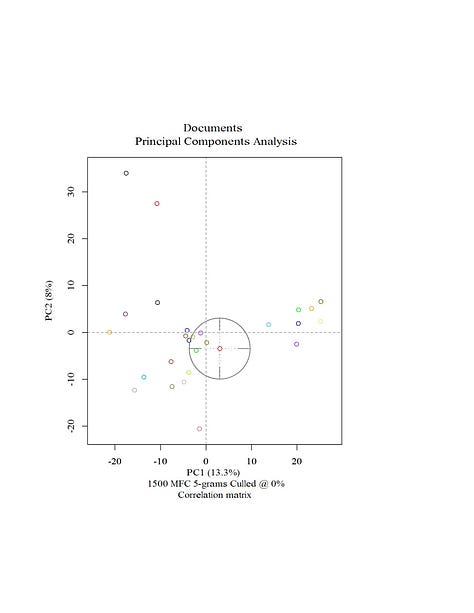

To make this analysis more robust, another common test to run is character n-grams. 3-grams in the word “Protocols” would be “Pro”, “rot”, “oto”, “col”, “ols”. 4-grams would be “Prot”, “roto”, ”otoc”, “toco”, “ocol”, “cols”.

When Prof. Patrick Juola, a stylometry expert, ran tests to find out if J.K. Rowling was writing as Robert Galbraith, character 4-grams were one of the tests he used. He cited a paper by Prof. Efstathios Stamatatos which demonstrated the effectiveness of character 3-grams. Another study showed that they are especially effective in the 4-8 gram range, with 500-3000 MFC. There is no hard rule as to what n to use, or what MFC to use, so I decided to run five tests at 3,4,5 and 6 grams, all at 1500 MFC. Again, I equalized the length of all works to the number of character n-grams in the Letter on Labor.

Here are the results, and you can again skip these if you would like, I’ll summarize at the end.

3g:

4g (Note: I discovered that I accidentally forgot to run the fifth test for 4g):

5g:

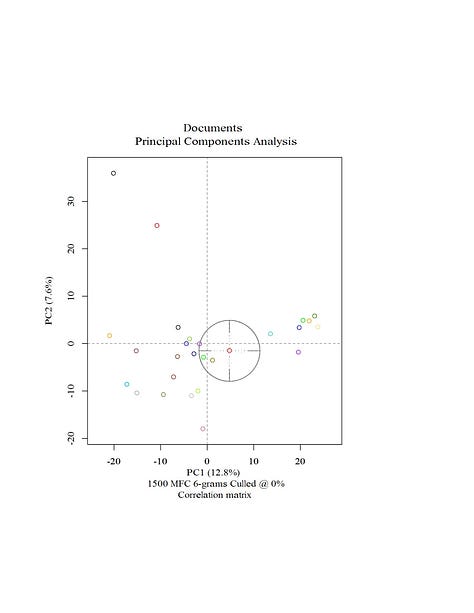

6g:

Results:

Balzac Labor: 15

de Maistre: 15

Veuillot: 13

Fourier: 10

Leroux: 8

Joly: 5

St. Bonnet: 5

Constant Spirit: 3

de Tocqueville: 2

de Stael French: 2

de Stael: 1

Guizot: 1

Say: 1

Constant: 1

Comte: 1

Again, Balzac tops the list, although de Maistre surprisingly ties it up. Veuillot puts in a much stronger performance, whereas Joly is much weaker. Fourier and Leroux put in decent showings both times. Here is the total of totals for both the frequent words test and the character n-grams:

Balzac Labor: 34

Fourier: 21

Joly: 20

de Maistre: 17

Leroux: 16

Veuillot: 13

St. Bonnet: 5

Guizot: 4

d’Aurevilly: 3

Constant Spirit: 3

de Tocqueville: 3

Guizot English: 2

de Stael French: 2

de Stael: 1

Say: 1

Constant: 1

If anyone would like to recreate these tests, I will mention again that the text files used are here.

It is possible that with enough searching, one might be able to find some work that just by chance more closely matches the Protocols, but the conclusion seems pretty clear that Balzac’s Letter on Labor is more stylistically similar to the Protocols than all 25 of the works in this corpus, and therefore it is probably more similar than roughly 95% or more of French political works in the same period.

When writing my original article and noticing such significant overlap in the ideas and phrasing of the Protocols with Balzac’s work, I could only think of one plausible alternative to Balzac’s authorship. That would be the possibility that some sort of Balzac imitator or superfan had written the document and extensively borrowed ideas and phrases from Balzac’s work. I still considered this possibility to be unlikely, given that the document appears to have been written by an experienced writer, not an amateur imitator, and the document appears to have originated in elite circles, with Eugene Sue probably being one of the first to possess it. Also, the Letter on Labor and Essay on Power were never published, so the parallels there would have to just be a coincidence.

With this analysis showing that the very structure of the writing so closely matches Balzac’s Letter on Labor, I think the possibility of an imitator can be almost ruled out. Consider that Balzac wrote little serious non-fiction, with the short documents I’ve used here being among the few examples, and even two of these were unpublished. The 1848 Letter on Labor does not match the 1833 Modern Government or 1841 Essay on Power at all, probably suggesting that Balzac did not write non-fiction frequently enough to even develop a style that would stay consistent through the years. Balzac’s fiction, which accounts for probably 95+% of his work, also does not match the Protocols. It’s possible that there are some political articles from Balzac out there that would be closer to the Letter on Labor, but it makes absolutely no sense that an imitator would decide to copy the style of some of his obscure and infrequent articles rather than the renowned Human Comedy. Even if they did decide to do that for some reason, I don’t know if there would even be enough material for such a thing to be possible without the aid of a computer. Copying a writer’s style on such a structural level is surely much more difficult than just borrowing their ideas and phrasing.

I’d like to end with a little change in my speculation. In my first article I speculated that Balzac gave the document to Dumas as a way of encouraging him to leave the Freemasons. I now think it’s more likely that he gave the document to Victor Hugo shortly before he died. Hugo recalls that they had a political argument:

This was the same room in which I had come to see him a month previously. He was then cheerful, full of hope, having no doubt of his recovery, showing his swelled limb, and laughing. We had a long conversation and a political dispute. He called me his demagogue. He was a Legitimist. He said to me, “ How have you so quietly renounced the title of Peer of France, the best after that of King of France ? “ He also said, “ I have the house of M. de Beaujon without the garden, but with the seat in the little church at the corner of the street. A door in my staircase opens into this church, — one turn of the key and I can hear Mass. I think more of the seat than of the garden.” When I was about to leave him he conducted me to this staircase with difficulty, and showed me the door, and then he called out to his wife, “ Mind you show Hugo all my pictures.”

I speculate that he may have realized he’d never be able to publish the document, and therefore decided he’d give it to Hugo as a last argument to leave in favor of Royalism behind him. From Hugo, it went to Sue.

It is frequently remarked on how Herman Melville died unappreciated and in obscurity, a major contrast with the renown that Moby Dick would achieve after his death. However, if it’s true that Balzac wrote the Protocols, I think it would be a far more remarkable story that an unpublished work of such a legendary writer would end up becoming his most famous, and in some ways define the 20th century without anyone even being aware that he wrote it.

Efstathios Stamatatos, “A Survey of Modern Authorship Attribution Method,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, vol. 60, no. 3 (December 2008), p. 538–56, citation on p. 540, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21001.

I haven't had time yet to read your long essay it's entirety but I'll just note after a quick glance that there are numerous ancient texts that use the format of briefly describing the contents of a chapter in a few short sentences at the beginning, Thomas Aquinas, if I remember correctly, uses that format